Looking at the list of artists who have appeared most often in global art biennials since the last Documenta, in 2017, it becomes clear the extent to which the Biennial World functions as its own, freestanding universe. It has its own concerns, and its own star system.

The names that dominate Biennial World are not at all the names that dominate Art Market World. In fact, the two worlds don’t seem to interact much at all, with the gallery-world sensations of the last five years—e.g. Amoako Boafo, Louis Fratino, Ivy Haldeman—having no special powers here.

Why the difference? I’ve been thinking about the film world as a useful parallel. Biennial Art is, to some extent, the equivalent of Festival Film. Just as a splashy biennial vernissage is thought of as the glitziest and highest-profile event in the art industry, the film festival red carpet defines a certain image of glamour for cinema.

And yet, the Venice, Cannes, or Berlin film festivals—or even the Academy Awards, actually, for all their Hollywood-centricity—have a funny relation to the mainstream of commercial film, existing as counterpoint as much as extension. They tend to honor works considered worthy rather than the blockbusters that will find a big commercial audience no matter what. Festival Film tends to be driven by social concern and topical relevance, to reward “actor-ly” work and modest experimentation—the kinds of traits that justify cinema as an art form and that play well to an educated audience.

So it is with Biennial Art. As anyone who has had to read a biennial catalogue or press release recently will know, it is defined, in general, by a sense of virtuous cultural consumption. So it seems that the list of the major biennial artists of the period will also be a portrait of how cultural virtue was defined in art in the last turbulent half decade.

.

Representation & Geography

A decade ago, biennials were reshaped by critiques of how representative they were. It became a journalistic ritual to count the ratio of male to female and non-binary representation, and to comment on the whiteness or Euro-centricity of the selection.

The tally of most-shown biennial artists is notably cosmopolitan in this regard, reflecting a diversity of geographies and backgrounds, but weighted towards the Global South. It may be emblematic that one of the most-shown artists on the global biennial circuit since 2017 has been the late Cuban-American Ana Mendieta, whose work was featured in the Athens, Berlin, Mardin, Shanghai, and Vienna biennials, as well as in the Kathmandu Triennial and in a show organized by Bienalsur in Montevideo. Overdue reckoning with the wrongs of art history has very much been on curators’ minds.

The upper echelons of the list feature artists like Erkan Özgen, based in Diyarbakir, Turkey (who we found in six biennials); Cian Dayrit, based in Rizal, Philippines (who we found in eight); and Tabita Rezaire, based in Cayenne, French Guyana (who appears on an astounding nine biennial lists in this period).

It is worth noting, however, that beneath the diverse backgrounds of the major biennial artists, a more traditional concentration of geographical power persists. Mapping out the places where the 75 top artists keep their studios (that is, all artists who made six or more appearances in these big art shows since 2017), a little more than half actually work in Berlin, London, or New York.

Interestingly, four of the top biennial artists either are now or have been recently based in Beirut, making it one of the notable geographic centers: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Marwa Arsanios, Ali Cherri, and Rayyane Tabet. That’s about the same number of artists in the top tier who say they work all or in part in Paris: Mohamed Bourouissa, Kapwani Kiwanga, Marinella Senatore, and Ali Cherri, again.

Despite its towering economic influence, China does not feature much in the top tier of Biennial Artists. The ultra-influential Zheng Bo, born in Beijing, is based on an island outside of Hong Kong. Cao Fei, who was in no fewer than seven different biennials, is the only top artist to work in mainland China (in Beijing).

Southeast Asia is much, much more visible on the biennial stage. Thailand, for instance, has been among the bases of operations for a large cadre of hyper-visible international artists. This includes one of the era’s biennial champs, Korakrit Arunanondchai (who we found in fourteen biennials in the last five years, and who curated his own Ghost Festival in Thailand in 2018), as well as Rirkrit Tiravanija (who turned up in six biennials) and Apichatpong Weerasethakul (who did seven).

If you are a painter, this has not been your time on the biennial scene.

Cecilia Vicuña may be the most prominent artist known for painting in the upper regions of the Biennial Artist ranks. Her witty and wonderful canvases, weaving together folklore and Latin-American leftist politics, recently had a starring role at the Cecilia Alemani-curated 2022 Venice Biennale (her art features as the official graphic, and she won the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement). This caps a period that also saw Vicuña appear in art events in Berlin, Gwangju, Kochi-Muzuris, Porto Alegre, Shanghai, and Villa del Rosario, Colombia.

But Vicuña is very much a polymath. In addition to performance and poetry, she is also known for her precario sculptures, “spatial poems” that bring loose collections of symbolically charged materials into mobile-like constructions, and her quipus, knotted rope works that recover a pre-conquest Andean system of writing.

Korakrit Arunanondchai also sometimes works in painting—in fact, a character called the “Denim Painter” is part of the dense, self-created cosmology of his work, and he’s created impressive installations in this guise. But it’s just one node in a larger practice. He is most visible for his spectacular video installations.

Scanning the biographies of the big Biennial Artists for keywords, “video” and “film” are far and away the most-mentioned media (followed by “installation” and “photo”—long before you find “painting”). Indeed, Arunanondchai is emblematic in his particular style of contemporary art filmmaking, a willfully fluid mix of personal material, world politics, Thai myth, and queer performance.

A style of digressive, lyric collage documentary blending fable and fact (usually with a hushed voiceover) is very much a dominant art genre on the Biennial scene. You can see similar impulses in figures like Thao Nguyen Phan, a star of eight recent biennials (as well as a member of the collective Art Labor, which was in four). Her video First Rain, Brise-Soleil mingled folk tales about a magic durian fruit, architecture history, and reflections on contemporary Vietnam at the current Venice Biennale.

At the same event, Ali Cherri—veteran of seven biennials in this period—spun together world myths and documentary images of mud brick-making and refections on the history of the Merowe Dam in North Sudan for the video Of Men and Gods and Mud, which won him the Silver Lion.

Beyond video, the other master terms in these artists’ biographies are “research” and “community engagement.” Neatly epitomizing this way of working is the other biggest recent Biennial Artist, the London-based Uriel Orlow, who ties Arunanondchai for most biennial appearances in this tally.

For the Lubumbashi Biennale in 2019, Orlow was commissioned to make Learning from Artemisia, a research project into the anti-malarial properties of African wormwood (Artemisia afra). The work involved him collaborating with a women’s collective in Lumata, Democratic Republic of Congo, planting a medicine garden and staging a community festival that included a song about the virtues of the plant by a local band. This then spun off into a traveling film and installation about the politics of herbal medicine in global capitalism.

.

.

Themes

The fact that Biennial Art has a bias for political themes is neither new nor news.

Writing on the Venice Biennale in 1999, New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl long ago diagnosed the rift between Market World and Biennial World, and coined the term “festivalism” for the favored mode of the latter: “environmental stuff that, existing only in exhibition, exalts curators over dealers and a hazily evoked public over dedicated art mavens.”

But the crisis-wracked last five years have put a particularly intense pressure on culture in general to deliver the political goods. So it is logical that art has been pressured to take these longstanding tendencies a step further, toward a steelier, less romantic form of intervention.

Surely the most symbolic example of this is the prominence of Forensic Architecture, the Goldsmiths College-based art collective which has exported its bespoke forms of art-as-investigative-journalism to events from Guatamala City to Palermo.

In fact, one of the most visible of all Biennial Artists here, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, also happens to be a research fellow for Forensic Architecture, and very much shares the model of “forensic aesthetics.” His searching investigations of the “politics of sound” were ubiquitous in this period.

Artist Susan Schuppli—another big presence at biennials, appearing at six different events—is also chair of the Forensic Architecture advisory board (and author of Material Witness: Forensics, Media, Evidence).

Works exploring the dynamics of cultural imperialism and legacies of colonialism were another major theme. (“Colonial,” “neocolonial,” “postcolonial,” and “decolonial” are among the most-used adjectives in biennial texts about these artists.)

Reckoning with colonialism is very directly the theme in the work of someone like Kader Attia, who not only was himself featured in eight biennials but is also curating the soon-to-open Berlin Biennale, which “looks back on more than two decades of decolonial engagement.” It’s also the concern of the 50-person Karrabing Film Collective from Australia’s Northern Territories, whose self-described M.O. is to use “the creation of film and art installations as a form of Indigenous grassroots resistance and self-organization.” It was featured at events in Jakarta, Gwangju, Shanghai, the Dolomites, Honolulu, and Brisbane.

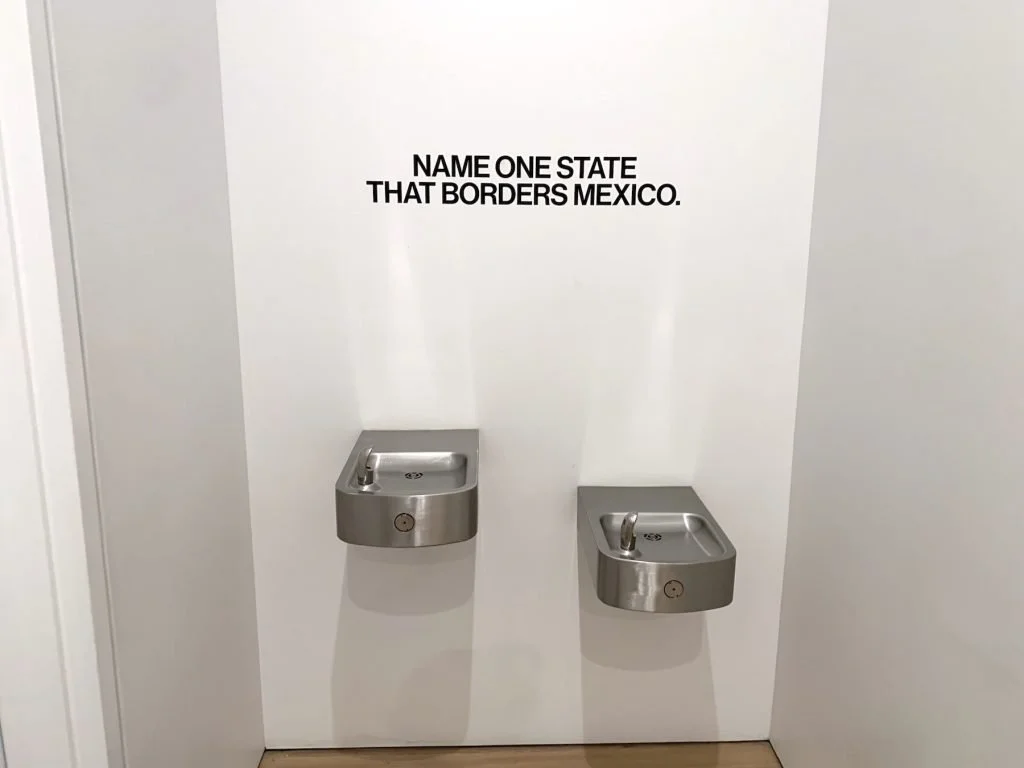

But it also runs as a thread through the work of biennial heavyweights including Monira Al Qadiri (who offered a recreation of an American-style diner at the 6th Athens Biennale in 2018, to provoke reflection on the impact of U.S. pop culture on Kuwait) and Cian Dayrit (who presented an installation of found military uniforms and trophies as a reflection on U.S. militarism at the 13th Gwangju Biennale in 2021).

Also ranking high are artists who warn of the dystopian side of contemporary technology (James Bridle, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Hito Steyerl). There is also a less outspoken strain of lyrical-but-crowd-pleasing science-project art. In this vein you have Ian Cheng, known for works incorporating arty artificial intelligence, and Tomás Saraceno, known for his love of spiderwebs.

“Art science” is also the mode of Marguerite Humeau, who works with researchers to create poetic riffs on zoology and deep history. Yet even given its engagingly far-out character, her experimental art’s popularity (eight biennials, including current bows in Venice and Sydney) is hard to explain unless you see how her fanciful installations refract what is, without a doubt, the single biggest big-art-show theme of the era: the environmental crisis.

(It says something that two separate figures atop our Biennial Artist list—Humeau and Superflex—have made work reflecting on the fate of the woolly mammoth. Humeau got her start recreating the sound of the extinct beast’s cry with scientists; Superflex hypnotized viewers at the Thailand Biennale to believe they were mammoths, to raise awareness about extinction.)

In big and small ways, art that imagined itself merging with environmental consciousness-raising was everywhere. Los Angeles-based Carolina Caycedo has presented works about struggles over water around the world, including at the eco-feminist-themed 15th Cuenca Biennial in 2021 and the 23rd Biennale of Sydney this year, which is water-themed. The Toronto Biennial commissioned London-based Shezad Dawood in both 2019 and 2022 to create chapters of his “Leviathan” series about climate breakdown. In between, he created a VR experience on the subject for the Folkestone Triennial in 2021, transporting viewers 300 years in the future to a flooded earth.

And it is probably a symptom of the spiritual tenor of the times that no fewer than two of the absolutely most visible, most in-demand Biennial Artists—Uriel Orlow and Zheng Bo—describe their work as pondering the “politics of plants.”

.

This is part of the Biennial Artist Project, a series on the stars of the biennial circuit. You can also read profiles of the top 23 artists and a report on the economics of being a biennial star. The full list of biennial artists (and which galleries represent them) is available to Artnet News Pro members.

.

.